(If you liked this page, then you might also like this page)

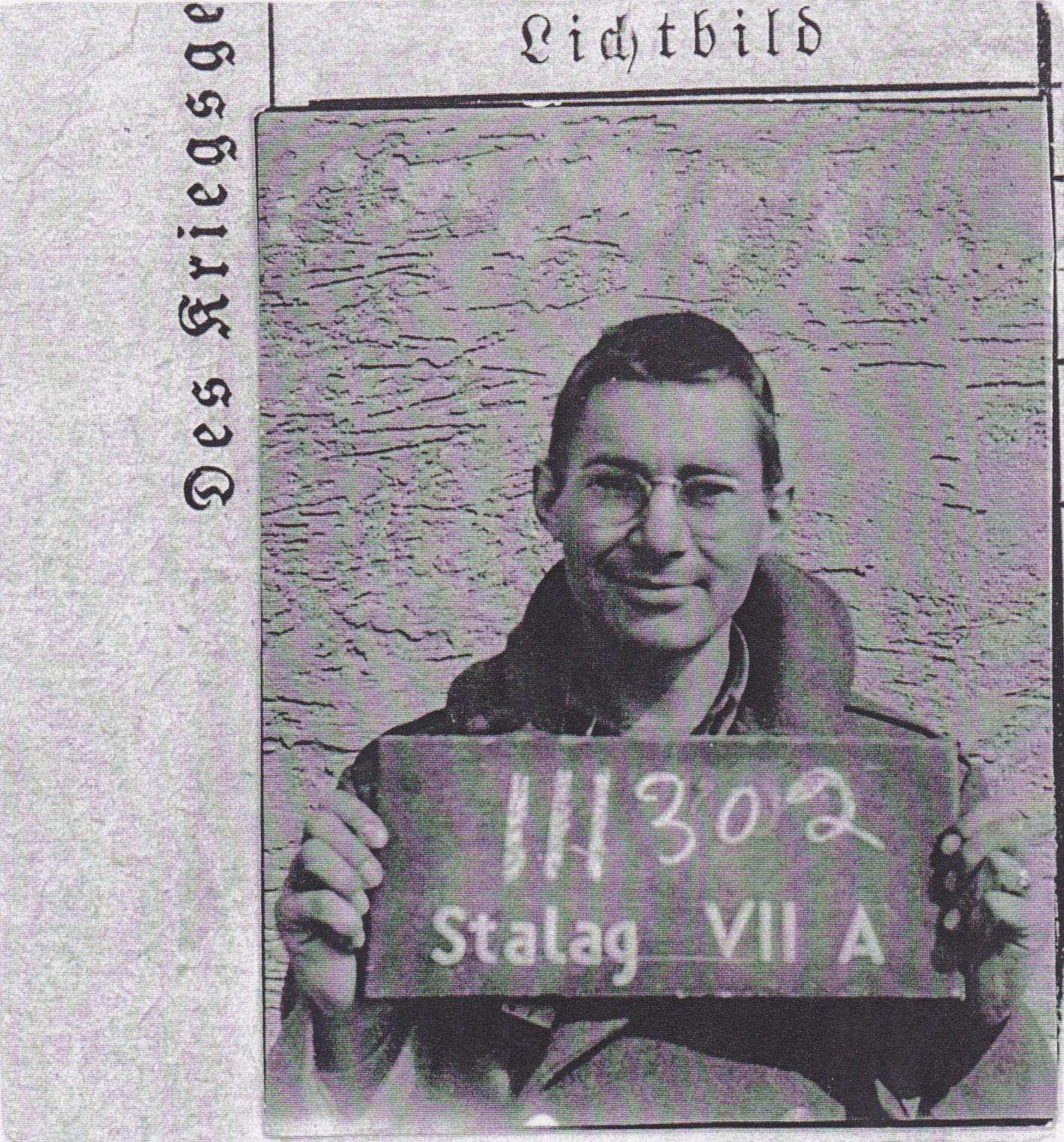

Wade Nyquist's Prisoner of War Papers

My Grandfather, Wade Walter Nyquist, was captured by the German army in Tunisia in 1943, and remained a POW until 1945. He was eventually persuaded by my Grandmother (Joyce Orth Nyquist) to recount the whole story so she could write it down.

At some point, my Grandmother typed up several copies of the original papers and passed them out to her kids. I found one of these copies at my Aunt's house, and scanned each page to have a digital copy for myself.

I have transcribed the text of Joyce's typewritten version here, and have made only very minor modifications. Specifically, I fixed any obvious typos / spelling mistakes (of which there were admittedly very few), and I have added chapter titles throughout to break up the story into logical sections. Everything else is exactly what Joyce typed.

You can also download the scans of the original typewritten pages, which contain some bonus photographs at the beginning and the end, lovingly assembled by Joyce.

Introduction

This is the beginning. If it is ever completed and if it is ever of value to anyone, it is because of the urging, pleading and entreaties of several people, the leader of which people is my beloved wife, Joyce, whose tenacity, once she gets the bone in her teeth, is truly awesome! For that and other reasons, these scribblings are dedicated to her, for without her, the task would never have been started.

Getting started is often the biggest job, especially for a 'put off until tomorrow' specialist.

Life before the war

Here is a bit of background. My father, Herbert Nels, was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1890 to Nels Nyquist and Matilda Johnson Nyquist. He went to school until grade 8 and then went to work to help his younger brother, Walter and his widowed mother. Nels Nyquist died November 6, 1894. Herbert eventually became a baker by 'heavenly intervention'. A load of lumber on a construction site fell 6 stories and missed him by inches. That's when he became a baker! My mother, Dora Alfreda Seaburg, was born on a farm near Villisca, Iowa in 1885 to Karl Otto Seaburg and Mary (Johnson) Seaburg. Dora and Anna were twins and part of a family of eight children, Fred, Dora, Anna, Esther, Clarence, Mabell, Ruth and Carl. Dora attended country school through grade 8 and during the summer months attended Swedish school where she learned to speak and write Swedish. At age 16, she and Anna went to Omaha where they lived with families and did housework.

My parents were married in 1912 and went to Pender, Nebraska to operate a bakery. My father tells of them, newly married, arriving in Pender where they were met at the train by friends with a wheelbarrow to escort the new bride to town. Mother was not impressed. Pender never was her favorite place. Two years later they moved from Pender to Neola, Iowa where they remained until my father's death in 1947.

Growing up in a small town was a carefree life. We were allowed a lot of freedom. My memories of my boyhood were of swimming in Mosquito creek on the edge of Neola, riding my bike, going to movies, playing baseball and as I grew older, working in the bakery. About the time I was in the seventh grade, a family with four children moved next to us. One of the children, Bill Witt and I became fast friends and for a couple of years, we were inseparable. Bill added a low to my experiences. He told me the 'unbelievable' facts of life. I never doubted what he told me because his source was an 'expert' - his 16 year old brother.

It was during these years that I remember my sister, Dorothy (the prettiest girl in town), who never suffered for lack of a boy friend. She was 1 1/2 years older by the calendar, but 5 years older by virtue of maturity. Bill Witt never could mature me fast enough to catch up with her.

My brother, Stan, who was 4 years younger, was just my kid brother until I came home from my first semester of college and was amazed at how he had grown up! It was reported by my mother that when the new baby was brought home, I looked over the edge of the bassinette and asked, "Is it ours?"

I graduated from Neola High School in 1936 and planned to go to the University of Iowa the following year. During the summer of 1936, my father became ill with high blood pressure and was ordered by his doctor to ease off on his work, so I decided to stay home to be of help at the bakery. I stayed for 2 years and then at the urging of my minister, Wilbur Swan, enrolled at Parsons College in Fairfield, Iowa. Looking back on that time at Parsons, they were really good years where I made many friends, some of whom I am still in contact. It was a time of trying my wings. I do wonder how I fit it all in. A typical day meant being up early and walking 1 1/2 miles to campus for a 7:45 AM class (there were very few cars on campus)- walking back downtown for lunch (the first 2 years at Parsons, I worked at a restaurant for meals) - then back to the campus for classes - then back downtown. Twice each week, choir practice in the evenings and three nights a week working at the restaurant from 6 PM to midnight. The first year at Parsons, five boys rented the upstairs of a house for $4 per person, per month. The second year I slept in the back of a barber shop. The third year I had a real 'cushy' job living with the sheriff and his wife. My duties were to help the cook feed the prisoners and answer the phone when the sheriff and his wife were away from the jail. And I thought those years were great!!!!

Called up for duty

In my third year at Parsons, I received notice that the National Guard unit, of which I was a member, was being federalized and that I was being called up for one year of duty. This was a real shock! It was with reluctance that I responded and found myself in uniform on February 10, 1941 and soon on my way to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. Claiborne was a bustling camp of tents where we trained intensively during the summer of '41. The army seemed unduly concerned about durability of shoe leather and was testing it to the fullest amount possible.

We remained in Claiborne looking forward to finishing our year and returning home. Then on December 7th, 1941, the Japanese changed the course of many lives by bombing Pearl Harbor. Within a month, we were shipped to Fort Dix, New Jersey, just a short commute from New York City. We were ordered to ready ourselves for a trip - nobody knew where.

On February 17, 1942, we were on the high seas headed east on the Duchess of Athol, a converted liner. The crew referred to her as "The Drunken Duchess". We found out later what that meant since the North Atlantic is pretty rough in the winter. The crew on the ship said we were going to Ireland where the grass was green and the girls were greener. We did not know 'why Ireland' - but the crew was right, we landed at Belfast on March 2nd.

We were transported by bus to Port Rush, a picturesque holiday town on the northern tip of Ireland. We were billeted in run down resort hotels overlooking a beautiful broad beach. We inquired about swimming and the Irish said, "Welcome to it - but stick your toe in first". It turned out the water is ice cold the year around. Port Rush is on a parallel with Hudson Bay.

We remained in Port Rush for 2 months and were beginning to make a life for ourselves when we were moved to Enniskillen in the south of North Ireland, where we stayed for 4 months. During this time, our training intensified, we were marching 10 miles one day, then 20 the next, then 10, etc., seven days per week.

From Ireland, we were shipped to Lughton, Scotland. Glad to leave all the tramping behind us -- little did we know!!

Scotland proved to be tougher than training in Ireland. We were doing amphibious landings, then climbing mountains carrying all of our equipment - then we walked back to our ship, reloaded and did the same thing over again about every three days. This was all done in drizzling rain. Our shoes, socks and clothing never dried for 6 weeks. With all this intense training, we knew we were landing somewhere on a 'hostile' shore - but nobody knew just where. Speculation, of course, was rife - if you had a theory, all you had to do was wait - it would soon be 'authenticated' by rumor.

About the middle of October, we were loaded on the transports and 'put to sea'. About November 1st, we rendesvoused with a huge convoy about 500 miles off the coast of Florida and it was announced that we were landing on the coast of Algeria. Much speculation about Algeria - where, what and why. The size of the fleet indicated something big. Ships were visible in all directions to the horizon.

Arriving in Algeria

On November 8th, we were off loaded on to landing craft and dropped on the beach at Sidi Ferruch, Algeria - without getting our feet wet! Our first encounter with an Algerian was a little Arab kid, begging for cigarettes. I held out the pack and he took the whole thing and ran. Resistance had been anticipated as light and it was in our sector. The fighting was heavy in the city of Algiers, but lasted only a couple of days, thanks to Gen. Mark Clark who was landed from a submarine on the Algerian coast to arrange with friendly French officers for their cooperation in the landing. We were transported into Algiers on day 3 and assigned a bank to guard against looting. During the night we heard a lot of gun fire from the docks, which were held by an American unit. They said the gunfire was from friendly troops blowing holes in huge wine casks with their 45s - then lining up to fill their helmets with wine. The wine was for 'export' - not all of it reached market!

We were stationed in Algiers at various places until about February 1, 1943, at which time we were transported to Tunisia where we were re-equipped with new machine guns and were stationed on top of Djebel Kasaira and ordered to dig in. The mountain (Djebel) was solid rock. Everything was peaceful for a few days - then the Germans began shelling our position. They were using flat trajectory guns and we were in ravines, so little harm was done. On the night of February 13th, we observed heavy traffic in the German area - column after column of trucks with their lights on! They had learned that a truck without lights can be more dangerous than our artillery. The next day, February 14th, enemy tank patrols began to appear. By midday, we could see heavy tank battles on the desert floor. The battle was far away - we had no idea of how it was going - or who were friend or enemy. After dark, there were many fires from burning tanks and vehicles. Viewing all the action from a mountain top was quite a spectacle. The next morning we began to see German infantry at the foot of the mountain and began to get a little rifle fire, which we returned. On the 16th, the Germans had mounted their mortars and were dropping mortar shells into our ravines. Late in the day we received orders to abandon our positions as soon as it was dark. We disabled all the equipment which we were leaving behind. Our platoon had carted our old four water cooled guns all over Louisiana, Ireland, Scotland and North Africa - then - just before going to the front, our old guns were replaced by new equipment which we decided to try to carry out. Each gun weighed about 100 lbs., so it was quite a load with our other gear. We were given a compass reading and strung out over the desert floor and told to form small groups and try to break out of our encirclement. It turned out that we had taken on quite a task - the Germans has surrounded us and gone on past us 50 or 60 miles so we had a good 2 day walk in enemy territory. We were tired, had not slept in 24 hours because of the mortar barrage, had been on short rations and were carrying no food. As the night went on, we became thirsty and drank the water from the machine guns, then disassembled them and tossed the pieces as we walked. Our new guns would kill no Germans!

Captured!

During the night, as we walked, we saw vehicle after vehicle and they were all American half tracks, tanks and trucks - so we began to assume that we were in friendly territory. As it began to get light, we noticed that there were camouflaged tanks just a short distance away. We also observed a strange vehicle coming down a road. We began to speculate about its nationality - someone said, "it's French", another said "English" and all the time the vehicle came closer. When the car was within 50 feet, the two occupants, each carrying a machine pistol, lowered their guns on us and ordered us to drop what weapons we had. By this time it was established that the men and equipment were German. The American equipment that we had passed in the night were shot-up tanks and trucks. The camouflaged tanks were German - we had stumbled into a German tank pool! The two men took us to the village of Sidi Bouzid where there we a couple hundred Americans sitting on the ground - under guard. As we waited - more prisoners kept coming in. It began to appear that we had suffered a major defeat. After an hour or two, we were ordered to our feet and marched down the road, headed east. We walked all day and into the night - we were all shuffling from fatigue and hunger. Finally we were directed off the road and into a field and ordered to lie down. The germans passed out cans of sardines to be shared - several men to a can - it was delicious! At daybreak, a column of trucks (captured American) were stopped on the road and we were loaded up and moved out. Later that day we arrived at Sfax on the Tunisian coast and our first barbwire enclosure, which was just that - a piece of desert with slit trenches for latrines, no structure or vehicles - just a teeming mass of men. We slept on the ground under one blanket, if we were lucky enough to have one. We dug shallow depressions to get out of the cold desert wind and doubled up to get more coverage. It was at this point that Bunny (Bernard) Schnitker and I joined forces and decided to keep moving to the back of the line where men were taken out of the camp for shipment elsewhere. We could hear occasional artillery and theorized that we might be lucky and be re-captured. The men moving out were forced to leave their blankets, so before they moved, we collected as many blankets as we could and finally we had a pile about 18 thick. If we had nothing else, we had sheer sleeping comfort.

Bunny and I stayed together through the remainder of the war. I couldn't have asked for a better friend. He was a guy who would do anything for you; would truly give you the shirt off his back and never get depressed, regardless of how tough and miserable conditions were. We stayed in that camp until everybody was moved out. We left our 18 blankets behind. There were many times when we joked about the 'luxurious' two weeks we enjoyed in Sfax.

From Sfax, we travelled via 40 & 8 cars (40 men and 8 horses) to Tunis, the capital of Tunisia. We were unloaded and marched through the streets of this ancient city which the Romans occupied and governed about the time of Christ. The Romans built aquaducts which are still used today. People who lined the streets were unemotional, neither smiling or scowling.

In Tunis we were 'stabled' in horse barns and discovered that manure, covered with straw makes a cozy bed. Our food, which up to this time was meager - improved. We were served bean soup which was given to us after dark. The skeptics said that was so we couldn't see the worms in the beans. I don't know if the Germans were that concerned - the wormy beans were real and were always consumed.

To Italy

Our stay in Tunis was brief, possibly 4 or 5 days. We were marched from there to the airport which was a bustle of activity. The Germans were in dress uniforms and were snapping to attention all over the place. A friendly driver of a staff car came up to us and in excellent English told us we were flying to Naples, Italy and all the activity was due to the arrival of General Kesselring. The general did arrive and such 'Heil Hitlering' you have never seen. Our friend, the staff car chauffeur, told us we would not be prisoners long because Germany had suffered a severe defeat at Stalingrad. If not accurate, the words were encouraging. We were loaded on JU52s which were the equivalent of a Ford tri-motor. We took off and crossed the narrow strait between Italy and Tunisia, leaving Africa behind. Our plane skimmed the Mediterranean - we could see every ripple. The Germans were trying to avoid the U.S. radar and did so, thankfully!

We approached Naples at dusk. As we passed over the city, we saw balls of fire coming up to us. The Germans thought we were American bombers. Our pilot was frantically shooting a signal pistol to indicate we were friendly. They apparently got the message and quit shooting at us.

So ended our African experience. The Battle of Fiad and Kasserine cost the Americans - 300 killed, 3000 wounded and 3000 missing in action. In his book, 'Kasserine', Martin Blumenson said, "Kasserine was where America lost it's innocence and began to realize the extent of the battle ahead of them". AS far as we, the 'missing in action' were concerned, who were considered 'seasoned' troops - we had trained for two years, we had suffered an ignominious defeat and were to spend twenty seven months in a POW camp. Fortunately we were so occupied with day to day activities that we did not dwell on the question of how long we would be POWs. Later on, after we were in a permanent camp, there was a lot of speculation concerning how long we could be prisoners and what the attitude of our country would be toward POWs. Russian prisoners, it was rumored, were executed by their government when they were repatriated. Since no Russians were being repatriated, it appears that that was pure speculation. It's doubtful that much sleep was lost over that rumor.

We were unloaded and taken to a POW enclosure in the dark - no lights because of blackout. We stumbled around and found tents in the dark and went to sleep. In the morning, we crawled out of our tent and there was Mt. Vesuvius smoking away. I think that was the only day we saw it - every other day it rained! It was at this camp that we learned the value of small things that we had taken for granted; in this case it was toilet paper - we had none, but soon learned that french 20 franc notes were ideal. It was here also that we rejoined our company. They were full of questions about where we had been.

I spent my 24th birthday in a sea of mud at the base of Mt. Vesuvius. Bunny got a job working at the kitchen and snitched a large block of cheese and passed it around. I accepted it as a birthday celebration. Bunny was an operator and often would be in a position to snitch food. On one occasion, he took a job helping a Polish priest who visited our camp to conduct mass. When we were getting ready to leave our camp at Stalag IIIB, the priest gave Bunny several bottles of communion wine to be used for non-religious purposes. The priest could have made a number of conversions that day!

To Germany (Stalag VIIA)

We were in the Italian camp for a few days - then were loaded onto 40 and 8 cars. The Germans put the load capacity to a real test - we didn't have the 8 horses and we did have so many men on board that only half of us could lie down at a time. We started to chug north through picturesque Italian countryside. We began to notice the difference after passing through Rome. There were more blonde people. As we got closer to the Brenner pass, the architecture changed to swiss chalets, the clothing to tyrolean hats and lederhosen. We passed over the Alps and into Austria. We were all impressed by the neatness of the countryside. Everything was orderly - the forests cleared of fallen branches and raked of leaves and needles. The scenery was beautiful. When we passed through the Brenner pass forty years later, we found the same contrast between Italy and Austria. The method of transportation left a lot to be desired. Having no sanitary facilities, we found a new use for our helmets. The problem was how to dispose of the contents since we had only one small window and it was barred. You can imagine the shouts of protest when an attempt was made to 'flush'. After 3 days we came to a stop at what appeared to be a real POW Stalag with guard towers and paved streets and flowers. We had arrived at VII A, one of the more liberal of German Stalags. We were unloaded and marched to the Australian compound where we were billeted with Australians. They gave us a hearty welcome and we were treated to the best we had eaten since capture. The Germans supplied soup, potatoes and bread. The Aussies, using their Red Cross parcels, had traded cigarettes, which proved to be the medium of exchange, for chicken, eggs, onions and many other niceties of life. It seems that the German commandant allowed a black market where one half day per week, the prisoners were allowed to leave their designated areas to go to a spot that could be used for trading. If you saw a Yugoslav with a couple of eggs, you would hold up the number of cigarettes generally traded for 2 eggs. If he nodded and extended his offering, you had made a trade. Stalag VIIA had many nationalities, Indians, Aussies, French, Yugoslavs and now - Americans. The Australians had been prisoners for 3 years and were receiving Red Cross parcels each week. The parcels contained 5 packs of cigarettes, 1 can of corned beef, a can of Spam, a small can of liver paste, a box of sugar cubes, a can of powdered milk, a can of Nescafe and 1 can of margarine. The Red Cross parcel with the German ration of potatoes and bread made it possible to be pretty well nourished. The Aussies had established a price list for all food items and did not deviate from it. They were in the driver's seat in controlling the market. With this set-up, we were hoping we would be kept at VIIA. Unfortunately, our hopes were not taken into consideration. On March 27th, we were told to move out and with much reluctance, we did.

To Stalag VIIIB

Our mode of transportation had not changed during our 9 days in VIIA, we loaded up and headed north. This trip was not quite so long, the plumbing was somewhat improved and we each had a Red Cross parcel which proved to be the last one until July. Our trip lasted 2 days and nights. When we stopped at Furstenburg and the doors were opened, we were happy to leave and were told by our guards that this was our permanent home, KRIEGSGEFANGENEN LAGER IIIB. We thought 'permanent home' was a little presumptuous and it did little to raise our spirits. The Germans were scraping the bottom of the barrel, our guards were the old, the lame and the wounded. We were lined up in formation and that's where we were introduced to the 'screamer'. He was in charge, REALLY in charge and LOUD. He was about 5 foot 2 and when he screamed standing with his arms stiff at his sides, he would walk along the formation. If you were a little out of line, he'd stomp on your arches and scream. We didn't know what he was saying but it must not have been good. We entered the main gate. Bunny said "Boy, look at the cigarette butts these guys throw away, life must be pretty good here!" He picked up a butt and discovered it was just a hollow cardboard tube. We later traded for some of these cigarettes because you could get twice as many - for a good reason. They were strong and cut all the way down if you inhaled. They were so bad - they cured some smokers of the habit!

The barracks at IIIB were brick and fairly new. We were in 20A right next to the Russian compound and soon discovered we could trade with the Ruskies for certain things. They would throw their item over the fence and if we wanted it, we'd toss a few cigarettes or food back. Mostly we bought coal briquettes from them or little items they made, like woodcarving or aluminum cigarette boxes. The coal was valuable for cooking. We'd break it into little pieces just right for heating a cup of water or frying some Spam. We had no cooking equipment. The Germans gave us one quart pot and one spoon and nothing on which to cook. Somebody invented a blower which was a squirrel cage fan made of tin from Red Cross food cans, which blew air through a can with a perforated bottom - creating a small forge. With a blower, a tablespoon of powdered coal would boil food in minutes. The Germans gave us a fifth of a loaf of dark heavy pumpernickle, 3 to 5 small potatoes and a cup of soup made from dehydrated rutabaga, potatoes or occasionally fish. Finding a piece of fish or meat was a cause for celebration! Our Red Cross parcels furnished not only food - the cans were hammered into dishes, pots, ovens, bread boxes, etc. Red Cross parcels were cardboard and not quite as large as 2 shoe boxes. The boxes were of value for storing our meager possessions. The cardboard boxes were shipped to us from Switzerland by the International Red Cross in wood crates with 2 end panels which were used by a group of volunteers who were skilled carpenters, actually skilled artists, who fastened them together to make dividing walls in a barracks, which the Germans allowed us to convert into a lecture room, a library, chapel and theater. The building was a 'bare bones' warehouse, about 160 X 40 feet and consisted of 2 barracks, one in each end of the building - the A and B end. My barracks number was 20A. The two barracks were separated by a common washroom with very cold running water. One end was used as a chapel, library and lecture room, the other end as a theater. The bunks, of course, were removed. With bunks in place, the A end would accommodate 120 and the B end 150, allowing about 24 sq. feet per man. The American compound had about 2000 men at the beginning in 7 barracks. The remodeling depended upon the arrival of Red Cross parcels, which did not happen until July. The project to convert the barracks into a chapel, etc. probably went on for a year. When complete, we had a beautiful chapel with a raised podium, kneeling rail, pump organ, oil paintings, by PWs and a large mosaic made from colored broken glass. The library had only a few books to begin with, eventually, we received books from the YMCA and at the time we left, there were several thousand dog-eared volumes. The shelves were made from Red Cross boxes.

The theater was a true work of ingenuity. It was in constant process of change due to different needs for different productions. One play, which was written by a PW required a revolving stage, which was designed by the stage hands. When the theater was in full operation, a production of some kind was put on once a week. The material for the proscenium, the stage, the mechanical devices to raise and lower, curtains and stage furniture mostly came from Red Cross crates and parcels, material generally considered junk. Very little trash was removed from the compound - uses were found for tin cans, cardboard and crating. The ingenuity of the PWs (Kregies) was amazing. Tin cans became dishes, cabinets, food grinders - you name it and somebody would invent it! The reputation of the productions spread to the camp commandant who attended with his entourage. Attendants at the door who had been warned beforehand shouted, "Attention!" Everybody would stand until the commandant and party were seated. Fortunately, the Germans did not try to require the hand salute and 'Heil Hitler'.

One of my interests was the camp chorus. We were fortunate to have a talented director, Russel Hehr, who before being drafted was assistant choir director of Trinity Cathedral at Cleveland, Ohio. We sang for some theater productions, at church services regularly and at other places, when requested. At one time we were taken to a work camp where some of our men, who were not NCOs worked. The truck we rode in was propelled by the fumes from burning kindling and we stopped about every mile to re-stoke the fire. Russ was a very talented guy - he provided us with many hours of pleasure while practicing for various productions. The chorus had about 20 members. Most of the music we sang was written by Russ, some original and some from memory. The charge for admission to the theater was cigarettes, which were used for bribery purposes to get things like paint, tools, some of which were forbidden. The classic example of the bribery power of cigarettes was when we bought a piano for the theater. It was loaded on a horse-drawn vehicle and placed in the theater by a 'bribed' middle camp officer. The German officers were very interested in the theater productions. We had one who often would stop to hear rehearsals and at times, offer criticism and suggestions.

Fortunately for us and not for them, the 168th infantry band was at the front doing their duty as stretcher bearers when we were captured, they along with us. When we arrived at Stalag 3B, we had a band - but no instruments. A request was sent through the channels for instruments and eventually, thanks to the Red Cross, Salvation Army and YMCA (God bless them all!), a shipment arrived with enough variety to equip the whole band. A lot of terrific music came out of that group and in addition to the military musicians, there were many others eager to exercise their talent.

Our medical facilities were somewhat limited. We had two medical officers who couldn't have been long out of medical school. They were the only two American officers in the camp. We sometimes felt sorry for them - they had no companionship, other than each other. They were not allowed to mingle with 'enlisted' men. They must have done a pretty good job - we did not lose an American from illness in our camp. Dental work was done by a squat Russian, who only did extractions. I had an infected tooth and reported it to him - he motioned me to sit (no English spoken here) on a heavy wooden chair. He stood behind me on a stool, put one arm around my neck, placed the pliers on the offending tooth (I hoped!) and pulled back and forth until the desired results were achieved - all without benefit of anesthetic. There were several men waiting in line for similar service. I'm sure they were somewhat discouraged about what they were in for. Nevertheless, they seemed to enjoy seeing me squirm. My other experience with health care was when I reported with a sore throat. The doctor took one look and said I was to be quarantined. He thought I had diptheria. I was sent to an outbuilding and completely isolated from the rest of the camp. It was the loneliest experience I'd had until then or since. My only contact was once a day when a Russian doctor with a long black beard came in and took a look, grunted and left. After I was there 3 or 4 days, another American was put in the opposite end of the barracks. We were not supposed to communicate. However, by shouting - we could understand and did talk back and forth. The next day, the doors were unlocked and we were in the same room. We must have spent nearly a week together. I had a book, Hugh Walpole's "Green Mirror", which we read to each other. Under ordinary circumstances, we wouldn't have touched it - but in these circumstances, it was a lifesaver!

The first summer at IIIB we heard distant bombing - then one day a large formation of planes, too high to identify, passed over. There were so many that their contrails blocked out the sun. Shortly after, when they were out of sight, there was a distant rumble. We told the guards it was American propaganda.

The favourite, always available recreation was walking. All during the day and evening - in twos, threes and more, prisoners followed the trip wire around and around in the sand, (one trip around was about a mile) discussing whatever you could imagine. When we didn't have food, the topic of choice was food - when we did have food, the topic was sex. The way to keep the hormones in check is to starve them! The approximate dimensions of our compound, which was a prison in a prison, were about 200 X 400 yards. At one time there were an estimated 5000 PWs in our compound, allowing about 16 sq. yards per man. The area we were confined in was not spacious. Occasionally, we were allowed to send a crew out of the camp, under guard, to grub tree stumps that could be chopped to use as firewood. The opportunity to 'get out' for a few hours made this a popular event, in spite of the hard labor involved.

During the summer months, the favorite participating and spectator sport was softball. There was a constant game every afternoon. Each barracks had a team, the teams were paired off so that everybody played everybody and we ended up with a winner of the World Series. Some very good softball was played and appreciated by players and spectators. The favorite card game was bridge. Many times, every table in the barracks was occupied in a bridge game. The 'purely spectator' diversion on a Sunday afternoon was to line up along the canal which was just outside our fence, and watch the couples walk along. Actually, we didn't watch so much the 'couples' as the girls. Somebody at the far end of the fence, perhaps 1000 feet, would say "Here comes one" and the word would be passed along. When the objects of the whole exercise was just opposite of where they could be seen, all action would stop on the inside of the fence, then as 'she' passed out of view, action resumed!

The daily activity that never varied was the count of heads at about 7 AM and 6 PM. The guards would come through the barracks blowing whistles and shouting, "Raus Raus, schnell schnell, Roll Call". We then would line up in formation, 5 deep, and if the count was correct, we would be released to go back to doing what we were doing, when interrupted. On those occasions, when the numbers were not right, we would be kept in formation until the missing person was found. It was a favorite pastime for a short person in the rear of the formation to duck down and go to the end of the formation to be counted twice. This, of course, was not done when the weather was bad - under those conditions, the delay it caused was not fun!

The most hated event was having to submit to a shakedown. Everybody would be called out and caused to stand in formation while the barracks were searched for whatever the Germans thought it was dangerous for us to have. We did have a clandestine radio and were able almost daily to get BBC news. The radio was so well concealed that it was never found.

We were at IIIB from March '43 to February '45, almost 2 years. That seems like an interminable time. As in other societies, we fell into the habits of performing our daily tasks and days slipped by. I spent a lot of time cooking when we had food. Cooking was mainly done outside over a 'blower', which was a little device made from cans to create a chamber to contain a couple tablespoons of cracked coal through which air was forced by a hand-turned crank connected to a squirrelcage fan. These little blowers created a fire like a blacksmith's forge. In order to make a blower, it was necessary to find a 1 X 6 board to attach it to. The only boards we had were the bed boards on which we slept. If you were too generous in the use of bed boards, you could end up falling through the cracks. The Germans did not look with favor when Hitler's bed boards were destroyed. Cooking under these conditions took a lot of time. At meal time, the area outside the barracks would be crowded as 'box buddies', one cranking and one tending to food, prepared the evening meal. When we were receiving Red Cross parcels regularly, they were issued twice a week to two men who shared the food and the preparation. At Christmas, a special parcel containing turkey, cranberry sauce and cookies was received with celebration. Our families were allowed to mail cigarettes and food parcels every couple of months. Needless to say, each time we received a parcel or letter from home - it was a 'red letter' day!

I spent a lot of time in the theater and chapel. At times, the chorus rehearsed daily before performing. Reading had always been a very enjoyable pastime. A record of most of the books read was kept and the list got to 98 when I quit keeping a record. My favorite reading was and is biographies. I read all 5 of Washington Irving's biographies of George Washington. Going over the list, the ten most memorable books were and are "Tale of Two Cities", "Three Musketeers", "Green Mirror" (of course), "Life of Washington", Vols. 1 thru V., "Magnificent Obsession", "Victoria of England", by Sitwell, "Drums Along The Mohawk", "The Robe", "Gone With The Wind" and "Mutiny on the Bounty". Bunny worked in the library and would tell me when new books were in. It pays to have connections. Books were supplied by the Salvation Army, YMCA and the Red Cross. A limited number of papers, The Volkisher Beobachter, were furnished by the Germans, but they were in German and 'slanted' unmercifully.

Sanitary conditions at IIIB were primitive, but reasonable. If someone neglected personal care, a friend would go to that person and suggest a bath and time in the washroom to help make life better for those around him. We had one guy who never took his clothes off to sleep. He was known as the 'best dressed man after lights out'. The Germans provided a shower with warm water about once a month. Meanwhile, the only out was to take a cold water bath, at zero degrees outside and no heat in the barracks - a 'bracing' experience! However, many did the cold bath bit. Our barracks had one toilet inside for 120 men. The main latrine was a 40 holer over a concrete pit, which at 'zero' degrees was also a bracing experience. There was little lingering in performing the daily dozen. Periodically, the Germans would send in a tank, pulled by horses and operated by a couple Russians on a hand pump, who, when their tank was full of 'honey', took it away and spread it on a field to enhance the next crop. We called it, what else - "The Honey Wagon".

During the fall of '44, the bombing raids were happening routinely, sometimes we could hear the explosions. We were only about 50 miles from Berlin. The clandestine radio reports were good. The Russians and Americans were both making progress. Red Cross parcels were coming steadily. Things were looking up. As our second Christmas approached, we were anticipating the 'special' Christmas Red Cross parcel. The Christmas spirit was evident everywhere. The chapel had a Christmas tree covered with tin decorations that looked terrific. The chorus was rehearsing Christmas music for a special program. Then -- it 'hit the fan'! The Germans broke through at Bastogne and for a time it looked like they might go all the way. We finally held them and forced them back and we were grateful. However, it did not help our plans for a special Christmas present - release from captivity!

Christmas came and went. The Germans were stopped at Bastogne, the special parcels came and the Russians were getting closer and closer. Toward the middle of January, we heard an occasional artillery rumble. We opined that it must be Russian, the news reports indicated they were approaching the Oder River. We were at Furstenburg on the Oder.

Marching to Stalag IIIA

On January 31, 1945, we received orders to move. We would travel on foot, carrying what food we had and our own blankets. We could expect to walk all night and perhaps longer. Anyone falling out of the column would be shot. You can imagine that threat kept us pretty much in line. I did not witness any shooting. There were reports of such things happening. It is understandable that we may not have heard a shot, the column was several miles long.

Weather for the 'walk' was not cooperating, there was a thick layer of ice on the roads, making for very slippery footing. In an attempt to ease the trip, many PWs were making sleds out of bed boards with the intention of loading everything on the sled. The theory worked until about sun-up when all the ice melted causing a re-arrangement of the loads. As in any trip, the tendency was to take as much as possible. Even though we had very little to worry about, when all your possessions must be carried on your back, it takes a lot of discrimination to decide what goes and what stays behind. Bunny took a brass cross, about 18 inches tall from the chapel and put it in his pack, vowing to save it at all cost. Many works of art were created by various PWs, paintings, carvings, tin can art, boxes, things that represented many hours of cutting, fitting, tinkering and painting. Many projects that were started to pass time turned into strikingly good pieces that, had they been taken back to the states, would have commanded good prices. Unfortunately, most of the items were left behind out of necessity. Many treasures, which started out on our trip, ended up littering our path from Furstenburg to Luckenwald (our next camp).

So - after nearly two years of confinement, we were to leave IIIB. There was an air of excitement in anticipation of getting outside the barb wire and having a change in scenery. We started late at night, slipping and stumbling - pulling a rag-tag assortment of home made rigs or knap sacks containing all our worldly goods. Food took the highest priority. The Germans released a Red Cross parcel to each man, in addition to what we had planned to carry, we each had that added load. If it became necessary to lighten the load, food would be the last thing to go. We walked all that night, and the next day. By mid-afternoon, the ice had melted, giving us a slushy footing. An improvement over the ice - but with wet feet. Just after dusk, we came to a small village and were met by a column of political prisoners in striped uniforms - shuffling rump to belly in lock step. When we tried to ask where we were, our guards became very excited and pointed their rifles at us and yelled, "Nicht sprechen". The two columns passed and we saw them no more. Seeing those poor emaciated men moving along in that fashion was strangely shocking and depressing. As bad as our situation was, we felt sympathy for them.

We passed through the village and by that time, we were doing a little shuffling ourselves. Our guards had not been relieved and were as exhausted as we were. It was a very dark night and men began dropping off in groups of 2, 4, and 6 and the guards did nothing. Bunny and I slipped into a grove of trees and with our overcoats on and one blanket on the ground and one above us, we slept the sleep of the exhausted - until day break.

As it became light, we discovered we were on a hillside along with a couple hundred other PWs who had done what we had done. We broke out some of our RC food and felt much revived. The guards were working up and down the road with the familiar 'los - los', which meant to move out. By the time the column was re-assembled, it must have been almost noon. A good number of men had slipped away during the night, deciding to try to contact American or Russian troops. We decided to stay with the column and achieve the same goal with the protection of numbers.

The march to Luckenwald was a couple hundred miles or more and took eight days. Along the way we bedded down where we could. One night in a brick kiln which was still warm from the fires used to harden brick - another night in a horse barn on top of manure, covered with straw - also warm. The most unusual nights lodging was in a Lutheran Church. We were taken into the church and told to bed down. There were no sanitary facilities in the church, so the guards allowed us to go outside and use the garden. When the minister's wife (we never saw the minister) saw what was happening to her garden, she raised hell and gave the guards some shovels to solve the problem.

Bunny and I were late getting into the church. Men were sleeping on the pews, on the floor between the pews, in the aisle - on the stairway and it appeared we were in trouble when Bunny said, "Hey - come here - I've found a spot in the belfry!". We climbed the stairs and dropped to the floor and were nicely asleep when the bell struck nine. We decided we could handle the bell once an hour and went back to sleep again. At 9:15, the bell struck one gong again and every 15 minutes thereafter. We decided it must be the minister's wife - getting revenge!

Marching to Stalag 483C

We finally made it to Luckenwald, Stalag IIIA and were marched to the American compound. The PWs who were there said they didn't know where they were going to put us since the barracks already held double the capacity. We finally found a spot on the concrete floor to spend the night. After a miserable night, we were awakened by the guards and told if 500 of us would volunteer to walk one more day, we would be put into comfortable barracks. Bunny and I and 498 others volunteered, feeling that things could not be much worse. As soon as we had our hot soup, we were marched out of the compound and headed for Stalag 483C, which we reached after a long days march. The guards had spoken truth. We were in wood barracks with bunks and straw mattresses. We had a wash room with unlimited water, sometimes it was even a little warm. We moved in thinking we had really struck it. After a nights sleep, we discovered that all was not perfect - the straw ticks were infested with body lice. Until then, that was one problem we had not had to handle. Every bad is balanced by good, however - we found that we could sit in the sun against the barracks, pull off our GI undershirts and hunt lice and pinch them between our thumbnails. It was something to do but it was not too effective in reducing the louse population. When we were liberated, the first thing the medics did was spray (DDT, I think) for lice. It was very gratifying to feel those little devils go crazy and stop doing what they were doing. We only had one treatment and had no more lice!

483C was a Stalag for Czechs. They were in bad shape, emaciated, sick and dying at a rate of a couple a day. The Germans would leave them lie in the street and every couple of days would bring in a horse-drawn wagon, toss the bodies in and haul them away. We were ordered not to try to communicate with them. We did find a way to pass cigarettes over the wall in the wash room. The poor devils would take any chance for a little food or a cigarette. Our RC parcels were soon used up and we had little to give them. The prospects of resuming RC contact we slim, but eventually we did get some parcels during the two months we were there.

We were in 483C when we got the news from the Germans that President Roosevelt had died. We requested permission to have a memorial service and it was granted. We formed up in what passed for a parade area and had a simple ceremony and a prayer. A year before there would have been no way we could have done that.

483C was between Berlin and Pottsdam. The British were bombing at night and the Americans by day. We always knew when a raid was coming because the guard dogs would begin to howl long before the planes came. They could hear the sirens before we could.

On Hitler's birthday, April 10th, the Allies really pasted Pottsdam. We had a makeshift bomb shelter and we spent a lot of time underground on that day.

Freedom! ... almost

About the last week of April, we were ordered to move again. We were hearing artillery bursts again from the east. The Russians were coming. We were travelling lighter this trip. The first day we ended up in Brandenburg and were put up for the night in a beergarden - sorry, no beer! We slept on tables or wherever we could. We got up in the morning and started out through the city center. We were stopped by a large public building when it was struck high up by artillery, which meant the Russians were nearby. The shelling caused a lot of excitement. Our guards took cover and disappeared. People were coming out in the streets carrying suitcases, wheeling perambulators, riding bikes, fleeing from the Russians. We joined the group and walked past the city edge into the country. Here we were, POWs walking along with the Germans, mostly women, and nobody paying the slightest attention. We passed a bar - men were going in empty-handed and coming out with a beer - so we decided to try. We did have some German money. We walked up to the bar, flashed our marks and said "Zwei Beer bitte". The bartender looked at us, shrugged his shoulders and drew two. As we sipped our beer, a German started to speak to us. He asked, "Fleiger?" We said, "No - infantry". He said, "British?" We said, "No - Americanish!" He said, "Got Himmel!". After our refreshing beer, we rejoined the flow of people. Traffic had increased considerably. We came to an intersection where there were guards separating the PWs from the civilians. We were directed down a side road. We walked until dark and stopped at a farmhouse where there were a number of French. We climbed up in the haymow and were nicely settled when someone from below said they had found a potato pit. The prospect of food got our attention. We followed a line of PWs who took us to a mound covering a pit which had been filled with potatoes in the fall and covered with straw and dirt. We took as many as we could carry back to the barn - washed them at the pump and had a sumptuous meal of raw potatoes and a rare experience - a full stomach!

We walked in a stream of PWs and refugees for about 3 days with German, French, Dutch, English and American - civilian and military, all heading west to get as close as to liberation and as far from the Ruskies, as possible. All this time, there wasn't a guard in sight. At the end of the 3rd day, we entered the outskirts of a village and asked a woman if we could sleep in her barn. She asked us to wait, which we did and she returned with two armed soldiers and the bergermeister. Our brief liberation was over!

The two German soldiers escorting us back to camp showed us leaflets they had picked up which were dropped telling of the advantages of surrender. They said they planned to do just that - but not right away. We tried to convince them to do it now and to take us along - but to no avail.

We were escorted to a PW compound, the most disorganized camp of several we had been in. At this stage of the war, the guards were more concerned about their fate than about guard duty. We were at that camp, I think it was XIIIA, for only a few days. They were fateful days, an event we had been looking forward to occurred during those days!

Freedom!

A British major was dropped by parachute near the compound. He made contact with that camp commandant and began negotiations for our release. Negotiations were complicated since we were 35 to 40 miles behind German lines and the commandant was reluctant to release us and ordered us to move out and walk to another camp. The British major jumped on an incinerator, about 4 feet from the ground and told us to sit down and refuse to move - that we were too weak to stand another march. The commandant ordered the guards to load their weapons - the Major told us to 'sit tight' and went into conference with the commandant and came back to us and said that they would bring in a German medical officer to determine how fit we were. While we waited for him, the word was passed around for everyone being examined to voice a complaint, real or invented. We spent the better part of a day going through the examination, after which the announcement was made that we would not be forced to march. The gutsy little British major had made his point! The following morning I was boiling water for tea over a fire when a jeep carrying two GIs pulled up in our area. One of them said, "Are you guys American?" We just stood there - stunned into speechlessness until we overwhelmed the two guys. About that time, a convoy of 6 X 6s drove up, each carrying white flags. Our Major had arranged for the convoy to come through the lines under a white flag. Score another point for the Major! When the order came to load up, we all piled in and moved out. As we left the camp, the Ruskies were tearing down the guard towers. As for us - we were numb - not quite believing what was happening - not celebrating - just trying to believe that these were American trucks and American drivers. We rode for 3 or 4 hours, passing through villages with white sheets hanging from all the windows as a symbol of surrender. We came to a check point and rolled right through without stopping. A long column of Germans were being checked through, walking, with all their possessions on their backs. In a field, right on the German lines, a baseball game was in progress. The reality finally sunk in -- WE WERE FREE!!!

Return to the U.S.

We were taken to a German airfield near Hildescheim and put in barracks for the night. We were sprayed for body lice, given new uniforms and fed and fed and fed! Most of us were lined up at the latrines giving up what we had just overeaten! From then on, we were given a diet of bland food and in limited quantity.

From Hildescheim, we were flown to Nancy, France - from there by train to Camp Lucky Strike, a major embarkation port for the U.S. We spent several days at each stopover and on about June 1st, embarked on the USS Searobin for home. She was a liberty ship and gave us quite a ride. Bunny was assigned a job in the galley, so we were well supplied with ice cream. The most memorable event of our trip home was seeing the Statue of Liberty in all her beauty in the New York harbor and being greeted by the fire boats shooting their hoses and blowing their whistles in welcome. It was June 11th and we were home after 3 years, 3 months and 25 days. Little did we realize the chain of events we were to form when we left the Duchess of Athol on February 17th, 1942.

As quickly as possible, we headed for Neola via a couple of camps that I no longer can remember. Our last leg was from St. Louis to Council Bluffs by train. We took a bus from Co. Bluffs to Neola and there to greet us, with a hug - was Grace Ryan, the postmistress and there in the doorway of the bakery was my dad, looking just as he had when I'd left. Back to SQUARE ONE. I think the bakery was closed that day. My mother was home - so off we went - the rest of the day was celebration!

I spent the rest of the summer in celebration! Friends streamed in from all over the world, some on the way from Europe to the Far East, since the Pacific war was still on. The bomb was dropped and the peace signed in August. I was ordered to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas on September 1st where I was discharged, after 4 years, 6 months and 14 days of military service, almost half of that time as a guest of the Third Reich.

After nearly three months on leave, it became apparent that at 26, still untrained at anything, it was time for me to resume the life I'd left in 1942. Fortunately, my situation had improved financially. During my PW days, my salary had continued and accumulated and there was the GI bill, which took care of tuition, books and lab fees and paid a stipend to live on. After long deliberations and the encouragement of Dr. John McVitty, I enrolled in the Illinois College of Optometry in Chicago in February of 1946. NICO offered an accelerated course, making it possible to do 4 years in 3 years by going to school without interruption - allowing me to graduate in September of 1948.

In addition to graduating - two events occurred during that period. A sad event, my father died December 26, 1947, as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage while I was home for Christmas.

The other event - a happy one! I met, wooed and won the hand of Joyce Orth. We were married November 27, 1948 and struck out for parts unknown. At that time, we knew not where we were going. In spite of shallow planning, things worked out well. We were blessed with 3 loving children, who are making a success of life. Optometry in West Point rewarded us well financially and made it possible to come in contact with many fine friends.

Many of the events I've discussed, compared to pictures of concentration camps as published by the news media may seen frivolous. My goal in writing my memories was to depict as accurately as I can remember how life was as a PW. It is difficult to put down on paper the frustration of being confined for 27 months - away from family, not knowing how they were bearing up, what kind of misery their imaginations were torturing them with.

We, as Americans, did have an advantage in being recognized by the International Red Cross. We had many PWs among us who were of German extraction, many who spoke German. The Russians had no Red Cross and no follow-up by their country. The Italians surrendered, leaving the Germans exposed, creating hate between the two. In their push to the south, the Germans never did capture and control Yugoslavia. These nationalities were represented in IIIB and were treated more harshly than Americans. Our major mistreatment was the skimpy diet of about 500 calories or less per day, consisting of 3 golf-ball size potatoes, a cup of soup and 3 slices of black bread. At the beginning of our imprisonment, we survived for about five months on the above diet and the 3 months at the end. The rest of the time, Red Cross POW parcels supplemented our diet. The RC supplement of food accomplished what it was designed to do - turn a starvation diet into borderline nourishment.

Keep in mind that a distinction was made by the Germans between political and military prisoners. The American Jews who were PWs tried to keep a low profile because of their exposure. The full horror of what actually happened was not revealed until Germany was invaded late in the war. We did not know the extent of the horror of "the final solution" - the gross numbers involved in disposing of millions of bodies. The Russians at IIIB were quoted as saying that 3000 of their group died from German Typhus (starvation) during the winters of '41 and '42. We witnessed mass starvation among the Czechs at Camp 483C where several men were dying every day and were dumped in the street.

CONGRATULATIONS to all of you who have plodded through this 'thing'. I find after writing this down, it reads like many things that we have talked over at the dinner table. That's the trouble with getting old - repetition - repetition - repetition!!!

The Joyce Orth Nyquist Papers

After reading these WPWP Papers, typing them and retyping them - I KNOW your next question is, "What about Joyce?" Always thought I'd write this down 'someday' when I had 'lived more' - but it has occurred to me that I have 'lived more' and it may not get any more exciting!

Believe it or not, Joyce has a life before Wade! I didn't travel the world for Uncle Sam or deal with 'prison camp' life, but I was alive and well during the war, in St. Clair Shores, Michigan, attending and graduating from South Lake High School (1943) and working in Detroit - but I've gone too far!

I was born April 16, 1926, the second and last child of Alma Theresa (Diamond) Orth and William Edward Orth. My brother, Douglas Eugene was 4 1/2 years older - old enough to be nice and tolerant. I have great memories of the years with an older brother - particularly when he was in high school and he needed a partner to practice 'jitter-bugging' - trust me, I was quite proficient by the time I reached high school! We both played Hawaiian guitars (yuch) and I took tap dancing, which I dearly loved. Four of us, Jeri, June, Nancy and I 'performed' and it came in handy during the war years for USO shows, etc.

I grew up on the Shores, about ten miles from Detroit on Lake St. Clair. Most of our summer activity was on or in the water and in the winter, ice skating (at which I was not good) and we foolishly 'tanned' all summer. We had part time jobs at Jefferson Beach, which was an amusement park with rides and of course, the beach. Doug worked as a life guard during the day and operated rides at night and I worked in the bath house checking clothes and as a relief cashier at night. All the neighborhood 'teens' did that in the summer - we were all within walking distance.

My father managed the A & P store for 13 years and then opened his own grocery store - not a good move since this was at the time when the 'super markets' developed. He sold the store in 1942 and went to work at Packard Motor Car Co. - everything became 'war effort' at that time!

I graduated in '43, but really left school (with enough credits) in January of '43 and went to work for the King-Trendle Broadcasting Co., WXYZ or the Blue Network (Soon known as the American Broadcasting Co.). They had called the school and needed someone with secretarial skills to work in the Traffic Dept. My job was to monitor the radio all day to see that the commercials were going on, as scheduled, type commercial copy and run the teletype machine. Did I feel grown up! I was sixteen but these were 'war years' and the boys went into the service as soon as they were 17 and the girls worked in the war factories if they were 18. WXYZ was exciting! The "Lone Ranger", with Brace Beemer as the masked man and "The Green Hornet" both originated from our studios. I lived at home and rode the bus into Detroit everyday - the ride along Lake St. Clair through Grosse Pointe every morning and evening was a delightful bonus. My brother was in the service, went into the army right after Pearl Harbor, went to Officer's Training School and spent most of the war in Utah and then the Phillippines.

Meanwhile, my parents decided to sell the house in the Shores and purchase some lake property near Alpena, Michigan on Hubbard Lake. My mother was one of 12 children and most of her brothers and sisters lived in the Alpena area. They bought a hunting and fishing lodge and named it BADJO LODGE, Billy, Alma, Doug and Joyce Orth! I was scheduled to move with them - I did NOT want to move up there so the radio station increased my salary (it needed it) and I moved into a Young Women's Residence Club just a block from the radio station right off Grand Central Park in Detroit, Michigan. I was a 'city' girl and I loved it! I was working at WXYZ thru the end of the war, VE Day and VJ Day - really exciting times - particularly at a radio station.

The war was over - the boys came home - great fun - the 'boys' had become 'men' and they had many stories to tell. They had become very 'serious' about life. But - I wanted to go into merchandising and I needed a 'on the job' training program and the two I knew about were at Bonwit Teller in New York and Carson, Pirie, Scott Co., in Chicago. I went to New York and stayed with a friend who was trying to break into show business (Nancy) and decided that N.Y. was not for me. Then I took another long weekend and went to Chicago and stayed with another friend (Eleanor) and was accepted into the executive training program at CPS. Attended classes 3 mornings a week and worked in Active Sportswear - Casual Clothes. What a match! I lived at the Eleanor Club, another women's residence club on the campus of the University of Chicago, took the IC to work on State Street in Chicago. I absolutely loved it! Met many fun people, was delighted to be working with clothes and was able to buy the clothes I wanted at great prices and had to dress well -- a dream come true!!

I met Wade in the spring of '47 -- he was the 'tall one' attending the dance at our club and after the third girl came up to my room to tell me about the 'tall one' - I went down and 'got' him in the 'broom dance'. Wade was living with six other Optometric students in an old mansion on the South Side (very 'seedy' by this time) and they had parties every Saturday night and I am not exaggerating when I say that we 'sang and harmonized' for hours every Saturday night. They had great barbershop voices and NEVER tired of it. On Sunday, he'd come over about 1PM (after dinner) and we would spend the day at the Museum of Science and Industry located right across the way from the Eleanor Club, in Jackson Park. The Museum was fascinating - always something new to see and it was FREE! Wade was really broke, really tall, and had a wonderful sense of humor. I had met the 'right man' and really was not ready for the right man!

Wade went home to Neola for Christmas in 1947 (his father died that Christmas, which I did not find out about until later) - four of my co-workers at CPS had an English basement apartment on the near north side and one was getting married so they needed another participant - so I moved in. I had decided that I did not want to deal with the RIGHT man - so when Wade returned to Chicago - I had moved!

But -- Wade appeared after 8 or 9 months - he was graduating from ICO, ready to start practicing the art of optometry and wooed me with roses and promises. Well -- I decided that even though I was not ready for marriage - I was old enough and this was the right man! We were married November 27, 1948 at St. Matthews Church in Herron, Michigan (the same church my parents had been married in 30 years before). Nancy Cummings was my only friend from Chicago to make the trip, Reona Kaiser, my cousin was maid of honor and Charles Rice, Wade's roommate from Chicago was best man. Very small wedding - with many relatives, aunts, uncles and cousins and Wade's mother from Neola in attendance. The reception was at the Lodge afterwards.

My 'hero' brought me back to Neola while he searched for the right place to open his practice and we moved to West Point, NE and opened the office on March 15, 1949. A great little town, less than 4000 population - some adjustment for a Detroit and Chicago girl! I had supported myself and made my own decisions from the time I was 17 years old - I was now 22!

The rest is history. We have 3 great children, Kristin, born December 8, 1949, Brian, born September 15, 1952, and Karl, born August 18, 1961. Feel that our greatest accomplishment was raising three responsible people, who married well and we now have 7 terrific grandchildren. I was a 'at home' mother and professional volunteer - church, Red Cross, church and civic boards, plus all activities connected with Wade's profession, state and national. Ask the Nyquist kids about the process they had to go through to get potato salad!

Wade's mother moved to West Point in 1960 and lived in an apartment on Lincoln Street until 1977. She really enjoyed West Point and made many friends there. It was always comfortable and pleasant to have 'grandma' in town.

We lived in West Point from 1949 until 1988 when we moved to Fremont, 30 miles away - back to my beach!! We had summer 'cabins' in the Fremont area from 1967 until we made the permanent move in '88. Wade was going to the office in W.P. two days a week when we made the move and he completely retired from optometric practice in December, 1991, after 43 years.

Now that's my side of the story! Wade was and is the 'right man'!!! We have been lucky!!

Herbert Nels Nyquist died in December, 1947.

Dora (Seaburg) Nyquist died in March, 1978.

William Edward Orth died in December, 1977.

Alma (Diamond) Orth died in March, 1986.

Douglas Eugene Orth died in October, 1993.

Wade Walter Nyquist died in May, 2000.

Joyce Orth Nyquist died in February, 2024.